Income Inequality and Investment

Plus accelerating services growth and productivity and drawing AI regulation lessons from other sectors

Happy Monday! In today’s newsletter, I look at the interaction of income inequality and business investment, touch on how to encourage productivity growth in services, and then highlight a report on how we can examine regulation in other technologies and sectors to guide regulating AI. I hope you enjoy it!

Income Inequality and Investment

I’ve been recently rereading Heather Boushey’s 2017 book Unbound: How Inequality Constricts Our Economy And What We Can Do About It. While heavily focused on the US, it nonetheless has so many interesting insights on the impacts of inequality more broadly. Given the ongoing arguments in Canada around capital gains taxation and how recent changes might impact investment, this quote on the arguments of John Maynard Keynes stuck in my mind. Keynes argued that:

in the long term, high inequality leads to the perverse outcome of having more savings available for investment but less incentive to invest. The implication is that places and eras with large gaps between rich and poor will see too little investment: "the richer the community, the wider will tend to be the gap between its actual and its potential production; and therefore the more obvious and outrageous the defects of the economic system," Keynes wrote. "Not only is the marginal propensity to consume weaker in a wealthy community, but, owing to its accumulation of capital being already larger, the opportunities for further investment are less attractive unless the rate of interest falls at a sufficiently rapid rate".

This seems worth pausing to think more about. Canada has struggled with low rates of business investment for a long time. This 2019 C.D. Howe Institute report, for example, highlighted how: “For every new capital dollar enjoyed by OECD workers this year, their Canadian counterparts will receive only 71 cents. And for every new capital dollar enjoyed by US workers, Canadian counterparts will receive a dismal 58 cents.” This was under the previous, more generous, capital gains regime of course. Meanwhile, as of last month, income inequality in Canada has reached the highest level on record, driven by the top 20 percent of income earners.

As Keynes argues, and as Boushey and many economists have backed up with substantial data, meaningfully reducing income inequality would be a powerful tool to increase business investment and help accelerate productivity growth.

Embracing Services to Boost Growth and Productivity

I touched on a piece last week on how we should think more about increasing the productivity of Canada’s services sector and growing our services exports. Given that services account for almost 74% of the Canadian economy - they receive startingly little attention.

In that context, this short piece from the IMF’s blog on how Asian economies can and should be embracing modern services is a particularly interesting read. In it, the authors note how modern services such as finance, information and communication technology, and business outsourcing have higher productivity and contribute more to economic growth than traditional services, and more than manufacturing.

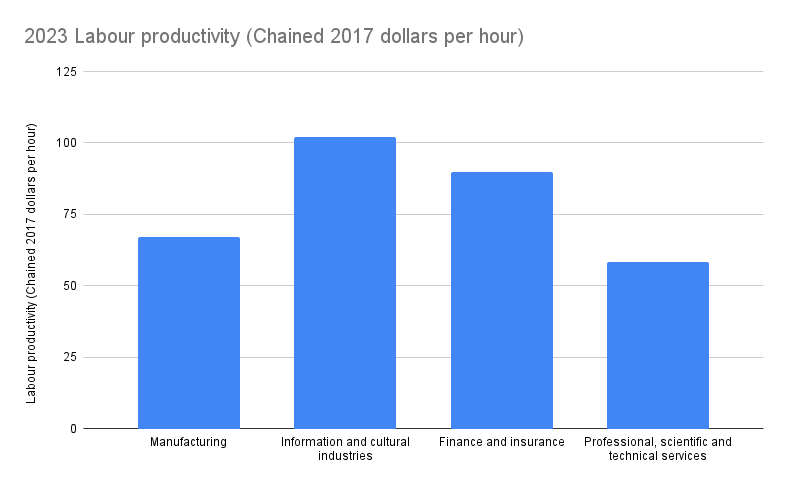

This holds broadly true in Canada. While the energy sector blows most others out of the water in comparison (though that isn’t a clear-cut picture by any means), comparing manufacturing to some modern services sectors looks like this:

Making more of our service sectors that have strong labour productivity would make sense, as would looking to identify the reasons why other sectors with trade potential, such as professional, scientific and technical services, are laggards.

As the IMF piece points out for Asian economies, unlocking services growth requires developing a digitally skilled workforce along with a big focus on removing non-tariff restrictions, of which Canada has plenty that hamper interprovincial services. An ambitious provincial or federal approach could go even further to support those sectors. This is an area I plan on writing more about soon.

Lessons for AI regulation from the governance of other high-tech sectors

Finally, I wanted to highlight this recent report from the UK’s Ada Lovelace Institute looking at AI regulation. It explores the regulatory structures, approaches and objectives of three other UK regulatory regimes: pharmaceuticals for human use, financial services, and climate change mitigation.

While they are certainly not a one-to-one comparison with AI, they have many regulatory functions aligned with those being talked about for AI. Furthermore, they note how “political economies of these sectors have similar dynamics to those of AI technologies, including the need to regulate a small number of powerful companies. These sectors share some common features with AI technologies, including opacity of how complex systems operate, the fast-paced development of novel products and a significant amount of uncertainty around their impacts.”

I think this kind of exercise is incredibly useful. Given the existence of “innovation amnesia”, which makes claims of a rupture from the past, this deep work looking at the continuity here can be a powerful tool to inform regulatory design and counteract that tendency. I’m not aware of any similar Canadian work but if you have come across any then please do reply and share it!