Understanding Canada's Challenges

Part 2 of my write up of my new report: Building an Innovative and Inclusive Canada

Happy Wednesday! Today, I want to continue my dive into my new report for the CSA Public Policy Centre, Building an Inclusive and Innovative Canada: Responsible Innovation for Shared Prosperity. You can find my write-up of the first few sections of the report here:

NEW REPORT: Building an Innovative and Inclusive Canada

I’m very excited that my latest report, Building an Innovative and Inclusive Canada: Responsible Innovation for Shared Prosperity, has just been published by the CSA Public Policy Centre. You can find it here on their website:

For a quick recap, in the first part of the report, I explored what innovation is, emphasizing that it is far broader than the narrow technological innovation that is so often the focus of Canadian policy decisions. Instead, innovation encompasses far more, including service and process innovation, diffusion and implementation, not just invention.

I then made the case that governments and other actors need to be far more focused on the outcomes of innovation. Innovation isn’t necessarily a good thing. It can be a net good for society, saving lives and improving living standards, but it can also do massive harm. You can’t just prioritize increasing innovation without a clear articulation of what the desired end goals are for Canada’s economy and society. We need a values-driven framework that can inform how governments and beyond think about and encourage innovation across all aspects of the economy and society.

Today, I want to write about the following section on the challenges Canadians face.

A Challenging World

We need a refreshed and values-driven approach to innovation, in large part because we face a difficult and challenging world. If we want a more prosperous and inclusive society, then whether and how we deploy innovative solutions to tackle these problems matters a lot.

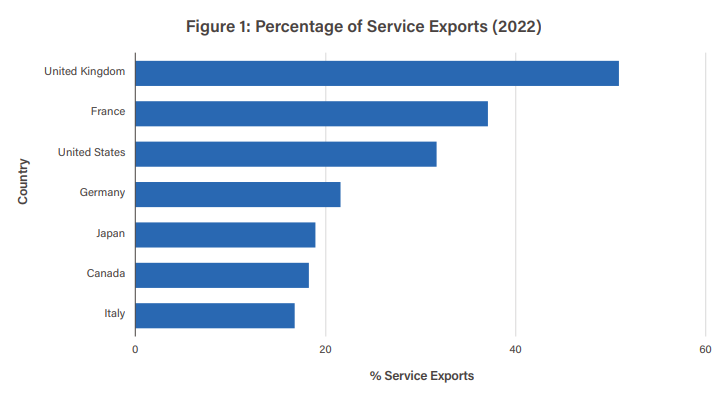

These challenges include a myriad of economic and social difficulties. On the economic front, Canada’s economy is still rooted in 20th-century modes of production, focused on resource extraction, but now with added financialization of housing sucking up investment and constraining innovation further. Canada specializes in low value-add parts of global value chains, low complexity goods, and has the lowest share of services exports in the G7 other than Italy, despite services being a key driver of growth in an age of fierce manufacturing competition. These factors all figure significantly into our continuing productivity slump.

On top of this, Canada’s economy remains deeply inequitable. While we might consider ourselves a more equitable country than the US, in reality, the gap is far less than we might hope - something Social Capital Partners’ Director of Policy Dan Skilleter highlighted recently:

In addition, we face other challenges. One is the uncertain impact of technological change, especially AI and its potential impacts on jobs and equality. This is precisely the kind of area where a values-driven approach that focuses on ultimate outcomes is necessary. As Burcu Kilic has also argued, Canadians must “set clear priorities to enhance domestic innovation capabilities to ensure that AI development aligns with broader economic and societal goals.”

Another challenge comes from wider, global innovation trends, such as the globalization of science and research, which extends to multinational corporations' offshoring of R&D in a similar way to how they once offshored manufacturing. This is a process that has been driven by declining research and innovation productivity. This is something I wrote about in the newsletter earlier in the year:

Rebuilding our Research Foundations

Happy Monday! Today, I look at Canada’s research landscape amid an unprecedented moment. Decades of underfunding, coupled with an underappreciated global decline in research productivity, have left us ill-prepared to take advantage of the research exodus from the United States. If we aren’t going to waste a golden opportunity, we need to look beyond pol…

Finally, we face even greater challenges from demographic shifts, climate change, and geopolitical competition—near and far from home. The latter two are among Canada’s biggest threats and have been the subject of enough commentary in this newsletter and elsewhere that I don’t really need to get into them here.

We cannot and should not attempt to understand our innovation policies and approaches without bringing them into this broader context.

These are major, even existential, challenges. How our governments respond to them, and whether innovation is pursued in ways that mitigate or exacerbate these challenges, will be crucial in shaping what life is like for Canadians in the coming years and decades. Reactive policy responses are insufficient to deal with this landscape. Instead, Canada must embrace a proactive, normative, and values-driven approach to policymaking, ensuring that innovation and economic growth serve the broader goals of social equity, environmental sustainability, and national sovereignty.

Unfortunately, as I’ll explore next time when I get into the next section of the report, Canadian innovation policy has focused on the inputs into innovation to the exclusion of these outcomes.