Today I want to do a proper deep dive into Canada’s approach to AI and our need for a more focused strategy. Back in the Spring, Budget 2024 announced $2.4 billion to support Canada’s AI ecosystem. Most notably, this included $2 billion to “build and provide access to computing capabilities and technological infrastructure for Canada’s world-leading AI researchers, start-ups, and scale-ups” - to be supported by a new Canadian AI Sovereign Compute Strategy. Other funding announcements were:

$200 million through Regional Development Agencies to support AI start-ups to commercialize their tech and to accelerate AI adoption in critical sectors

$100 million through IRAP’s AI Assist Program to help SMEs scale up and increase productivity by building and deploying new AI solutions.

$50 million for the Sectoral Workforce Solutions Program to provide skills training for workers in potentially disrupted sectors and communities

$50 million for a new Canadian AI Safety Institute to further the safe development and deployment of AI; and

$5.1 million for the Office of the AI and Data Commissioner to strengthen enforcement through the still-not-passed Artificial Intelligence and Data Act.

These investments are on top of $443 million committed to Phase 2 of the Pan-Canadian Artificial Intelligence Strategy that funds the three national AI institutes, Scale AI, CIFAR’s funding for AI academics, and more.

Now, what should be clear from that is Canada has made commitments on a huge range of areas. From early-stage academic AI research, through building Canadian-owned and located AI infrastructure, commercializing AI start-ups and scale-ups, and advancing the adoption of AI in other sectors, while mitigating the impacts on workers.

That’s a lot.

And it’s not much money to do that.

The Compute Conundrum

How to spend the money for compute illustrates that. $2 billion is a drop in the water even if you are focused on just supporting one leading-edge company. OpenAI, for example, is projected to spend $7 billion USD on training new models and on inference workloads for ChatGPT. Anthropic expects to spend $1 billion USD training this year’s AI model, with their CEO expecting the next generation will cost closer to $10 billion USD. Canada’s funding meanwhile is designed not just for one firm, but a big pool of “AI researchers, start-ups, and scale-ups”.

Unsurprisingly, this is causing some problems. Murad Hemmadi's great article in Logic this week highlights some of the tensions. Some AI firms, such as Waabi, are arguing that only foreign cloud services, (e.g. AWS or Microsoft), offer the capacity they need to train models and government funding may be needed to subsidize startups to buy compute from them. Chip firms, on the other hand, argue for “buy Canadian” requirements to enable sovereign Canadian infrastructure.

There are then further disagreements over who should be prioritized. The co-founder of Reliant AI argues for focusing funding on firms “that are just getting started with the compute they need to try out their ideas”. David Katz, a partner at Radical Ventures, instead supports the idea of Ottawa offering larger pay-outs to companies scaling their models to sell to clients where the cost of compute is its most prohibitive. Still others argue that support for Canadian “mega-models” is unlikely enough to help them catch up to Silicon Valley firms and, instead, the focus should be supporting firms such as Ada that use other firms’ AI models and customizes them to help organizations adopt them. The article doesn’t even get into how much of the funding should go towards academic AI research and not-for-profits that can struggle to access sufficient compute even more than private companies.

Where are we playing to win? Because it can’t be everywhere

This speaks to the lack of a focused strategy and vision for AI in Canada. By trying to play all across the value chain, we might end up losing all of these bets.

We need to be realistic. Canada is a little over 1.3% of the world economy and around 0.5% of the world population. Expecting Canada to be a major player across all parts of the AI value chain is doomed to fail. The image below from a Frontier Economics analysis of the EU’s positioning in critical technologies provides a simplified version of the global value chain for AI:

Note that no Canadian companies are highlighted as leaders across any part of the value chain.

Some of the more detailed analysis in that report shows some areas of Canadian strength, but also how far behind we are in others. While Canada is third for AI publications and leading AI publications per million people, in raw terms Canadian academic output is far outstripped by China, the US, and the EU. And that is the good news. When it comes to patents filed per million people, Canada lags South Korea, Japan, Hong Kong, Taiwan, the EU, the US, Israel, Switzerland and Singapore. Andw while Canada has a lot of funding for AI companies, this has translated into a minuscule market share of the global value chain (Figure 2).

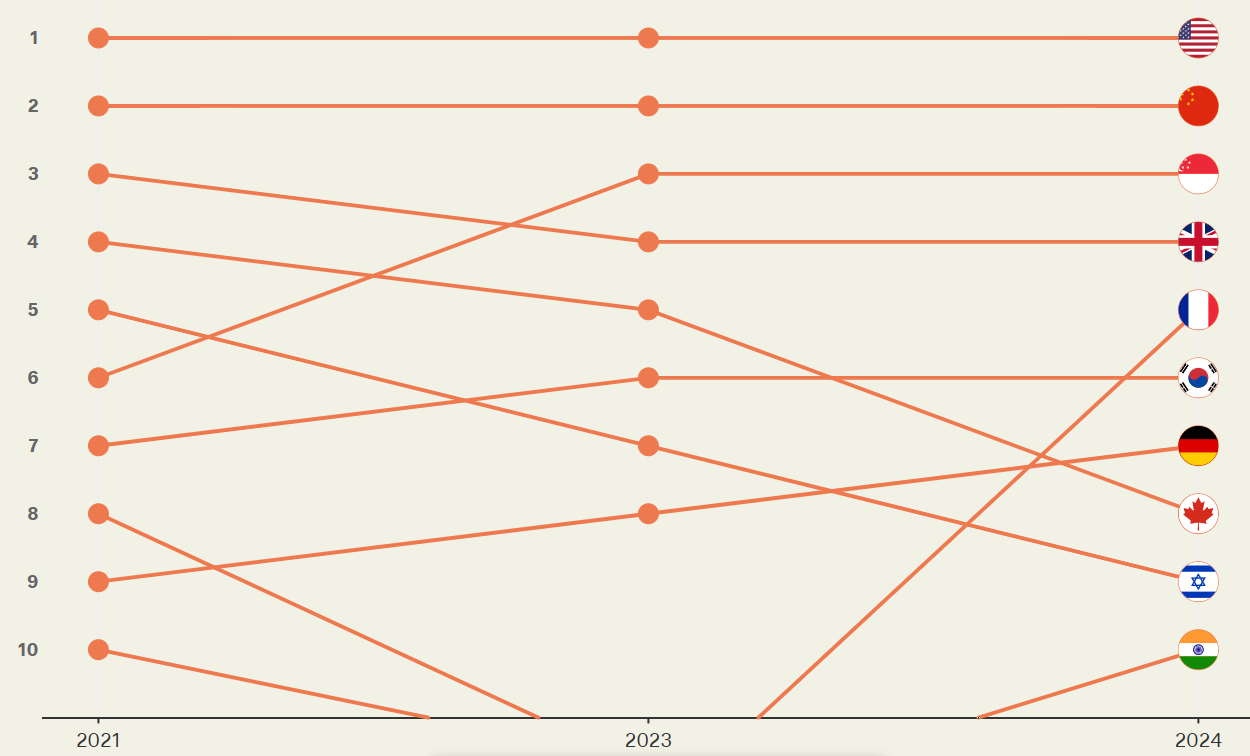

This lack of focus will have consequences as we waste the advantages Canada has. While Canada was the first mover when it came to having a national AI strategy, most countries have gone far beyond that now. We are already slipping in global AI rankings, as this from Tortoise Media from September shows:

Make the Difficult Decisions

If Canada is going to win in AI then we have to make some difficult decisions. We don’t have the resources, in talent, companies, research, or federal funding, to win everywhere. We won’t have world-leading Canadian-owned computing infrastructure, and world-leading Canadian AI researchers, and world-leading Canadian-owned start-ups, and world-leading Canadian-owned foundational AI models, and world-leading AI adoption by other Canadian sectors. Certainly not for under $3 billion over multiple years.

Some of the underpinning assumptions are questionable too. Jake Hirsch-Allen and Graham Dobbs argue that “even in the long term, AI Compute sovereignty may not be fully achievable, and it may not be worth the cost—we will continue to be interdependent with supply chains and providers housed outside Canada”. We need to play where we can win - and this should be aligned with a vision of what we want Canada to be.

To guide these decisions, I come back to this need for a vision of Canada’s economy in 10-15 years. For me, I think we should ground this in building an inclusive economy. Taking a definition from the Rockefeller Foundation, an inclusive economy is:

Equitable - with opportunities for upward mobility for more people and inequality declining.

Participatory - with people able to participate fully in economic life as workers, consumers, and business owners and with technology widely distributed and promoting greater individual and community well-being.

Growing - with the economy producing enough goods and services to enable broad gains in well-being and greater opportunities, including growing incomes, especially for the poor.

Sustainable - with economic and social wealth sustained over time, maintaining inter-generational well-being, and preserving the natural world’s ability to produce ecosystem goods and services that contribute to human well-being.

Stable - with economic systems resilient to shocks and stresses, and with people having confidence in the future and an increased ability for people to predict the outcome of their economic decisions.

We should see how funding for AI matches up against those principles. Some aspects don’t mesh well. For example, the huge environmental toll of large AI models has been widely reported, with GPT-4 using up to three bottles of water to generate 100 words, and with data centers accounting for a rapidly growing share of global energy consumption.

What then is an AI strategy that takes into account sustainability? Maybe it is priority funding for firms that are working to reduce the computing power needed to run large models or that are focused on technology to make data centers more efficient. Perhaps even drawing on Canadian strengths in Small-Modular Reactors is a logical focus, at a time when big tech firms are turning to nuclear power as a zero-emissions source of energy for their data centers. Exporting SMRs that are tailored towards data centers, with the ongoing services required to maintain and operate them, could be a reasonable place for Canada to own part of the AI value chain.

There are also challenges from AI to an equitable and participatory economy. These aren’t inherent in the technology itself, but in the business model around them, as Nobel Prize-winning economist Daron Acemoglu discussed on last week’s excellent CIGI Policy Prompt podcast. As he pointed out, when it comes to AI in education, current investment is for models that prioritize automation of content, grading, and tests. This is an approach geared towards cost-cutting. Acemoglu highlights another scenario where generative AI is used to personalize education and empower teachers to use it to address the difficulties of specific groups of students, changing the content and the way it is delivered to have more effective teaching.

This kind of empowerment of workers - to improve outcomes rather than just cut costs - is where there is huge potential but it doesn’t fit neatly into Silicon Valley business models. It is, however, an area where federal funding could make a difference, especially when combined with leveraging the power of procurement to provide markets for innovative technology that tries to do things a different way.

Making choices like this will inevitably mean that some parts of the AI ecosystem in Canada aren’t supported. And that is fine. There is still a market economy out there and firms can and should sink or swim on their merit. Not every AI subsector can be supported in this kind of targeted way. Other types of horizontal supports are still there, such as SR&ED, and it is entirely appropriate that the government continues to provide them.

But when it comes to specific AI funding, choices do have to be made and they should be informed by the vision of the economy we want to see for Canada.

We have done it this way (wide and shallow) for too long. That is the risk aversion aspect of bureaucracy. Don't bet big on what might be a losing horse. Smaller bets across the board hedge for those losses, but we miss out on the wins. And to your point, might mean an overall loss.

I do think your point about SMRs makes sense. Stable, GHG-emissions free(-ish) energy would make other business models more viable in the long run. That said, the US is quickly eating our lunch on that front with far more money pouring into SMR vendors at the moment, and with recent setbacks in Canada regarding our own potential SMR technologies, hopefully we don't fall further behind.

Hopefully, the BWRX at Darlington starts building this coming year and that unlocks more appetite for nuclear support and the funding it truly requires.

What are the barriers for Canadian SMRs? Is it a case of government funding for R&D and procurement or a lack of investment from power companies? Or something else entirely?